There’s a rare lull in the breakneck world of independent science fiction, so while the New Release feature is catching its breath for a couple weeks, let’s look back at the pulps.

What is pulp fiction?

That is a loaded question, as pulp fiction encompasses many different genres. Science fiction, hard-boiled detective stories, heroic crime fighters that would inspire today’s superheroes, sword and sorcery, and the awful menace of the weird lurking around every corner. And those are just the genres created in pulp’s golden age. Pulp fiction also featured detective cozies, romance tales, westerns, historical adventures, war stories, horror, and more all served up by the dozen for a dime or a quarter per customer. Because of this stunning variety in genre and style, many critics shrug their shoulders and say that pulp fiction is fiction that was published on pulp paper.

That is a loaded question, as pulp fiction encompasses many different genres. Science fiction, hard-boiled detective stories, heroic crime fighters that would inspire today’s superheroes, sword and sorcery, and the awful menace of the weird lurking around every corner. And those are just the genres created in pulp’s golden age. Pulp fiction also featured detective cozies, romance tales, westerns, historical adventures, war stories, horror, and more all served up by the dozen for a dime or a quarter per customer. Because of this stunning variety in genre and style, many critics shrug their shoulders and say that pulp fiction is fiction that was published on pulp paper.

In other words, a medium, not a genre.

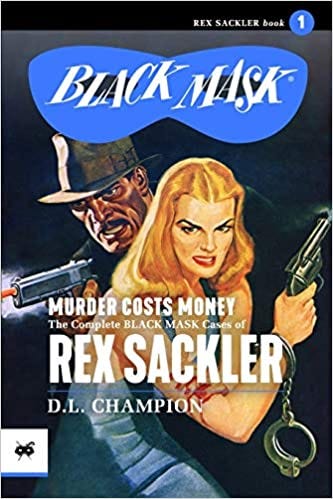

The name comes from the paper these stories were written on. Cheap, rough, low quality. Pulpy. Completely different from, and some atop their ivory towers would say inferior to, the slick quality of the magazines used for proper literature and proper stories. Such elitist still drips from pulp’s critics today. But when H. L Mencken needed money to support his high-brow literary magazine, he turned to the pulps and founded Black Mask. Mencken’s literary journal was saved, and Black Mask went on to found literary genres, writing styles, and even film noir.

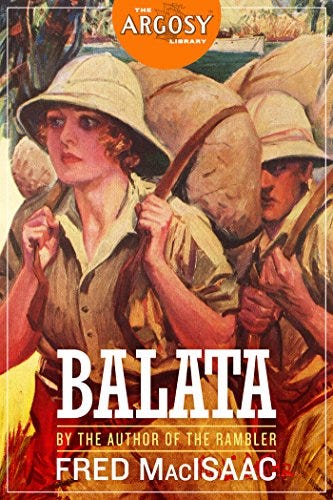

Pulp publishers could be fly-by-night as they chased success. The average pulp imprint lasted little over a year. Some, no longer than an issue. This volatility forced pulp writers into writing self-contained short stories. And if a character was popular enough to warrant a return, the following stories were episodic. Gone were the serials, as unless a writer was fortunate enough to write for stable and successful magazines like Argosy, there was no guarantee a magazine would survive to the serial’s conclusion.

But 1940s wartime shortages moved many pulp magazines away from pulp paper and into the digest format. The paper might have changed, but the stories did not. So something essential to these stories continued to survive in this new medium. And, indeed, continues to do so, as German science fiction serials, American men’s adventure, African photonovels, and Japanese light novels all contain elements of their pulp fiction forebears. Even today, many look back to the golden age of pulp fiction for inspiration in storytelling, style, and milieu. Call it neopulp, dieselpunk, Pulp Revival, or Pulp Revolution, if you wish. The spirit of pulp fiction still lives on.

Despite the abundance of style and genre, certain common features of pulp fiction can be determined.

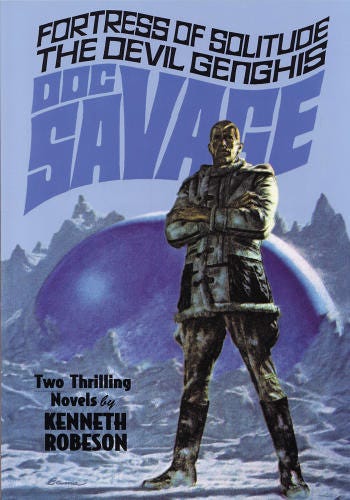

Pulp fiction is short fiction. Even the pulp novels, such as in the hero pulps like Doc Savage and the Shadow, are closer in length to today’s novellas than even today’s shorter novels. This means that pulp fiction taps into that American literary tradition that began with Edgar Alan Poe: short stories of mysteries and the weird. Expect twists. Make sure you read to the end, as the last lines might change the entire context of a pulp story.

Pulp fiction revels in the exotic. Far away places, far away times, secret societies, hidden underworlds. Any new setting fundamentally different from the apartments of Chicago and New York. Classic settings included French Foreign Legion tales of Africa, the vast chinoiseries spanning from Byzantium, Damascus, Dehli, Peking, and Tokyo, the American frontier, and Western European history. And when exotic locations would not suffice, exotic occupations filled the bill: gangsters, G-men, pilots, sailors, travelers, and detectives.

Pulp fiction demands verisimilitude. These exotic locations, jobs, and people need to be conveyed with the convincing appearance of reality. Even is such imaginary places as Clark Ashton Smith’s barbaric future continent of Zothique. While this verisimilitude may be more forgiving than the exact correspondence to period and reality demanded by many of today’s readers, pulp fiction does not have the time or the wordspace to go into lengthy descriptions or explanations of clothing, culture, or equipment. Make sure you bring a dictionary when reading a pulp historical.

Pulp fiction is adventure. Even the more comedic stories, such as W. C. Tuttle’s Sheriff Henry, are built around exploring the unknown and facing the perils along the way. Adventure may be far away or around the nearest corner, both hidden behind the thin veneer of polite society. Thanks to Lester Dent’s classic Master Plot, a pulp hero can be expected to face some physical peril with almost every turn of the page. And each peril may usher in some new twist that pulls the hero into a new direction—and a new peril.

Pulp fiction is decisive and demonstrative. Unlike today’s stories, where the protagonist spends 80% of the story building up to making the correct choice, a pulp protagonist makes his choices immediately and acts upon his decision. The remaining 90% of the story is devoted to the consequences of said decision. These consequences, many unintended, prove the rightness of the protagonist’s decision. Or disprove, as weird/horror writers, such as Manly Wade Wellman, started their horrors with poor choices by a hapless soul. After all, the road to Hell is paved with good intentions, and a choice is justified by its outcome…

Pulp fiction is not low quality. The lean, swift prose popularly known as the Hemingway style comes not from Ernest Hemingway and his daiquiris, but from Dashiell Hammett and his fellow contributors to Black Mask—as critic Gertrude Stein said after Hammett’s Maltese Falcon was published. Walter Gibson crafted a distinct brooding style for the vengeful Shadow. Clark Ashton Smith’s Zothique tales are beautiful in their descriptions of the weird. Ray Bradbury wrote his stories so vividly that Edmond Hamilton declared them not to be science fiction, but too wonderful not to be included anyway. The Queen of the Space Opera Leigh Brackett would team up with William Faulkner to write the script for The Big Sleep, adapted from pulp writer Raymond Chandler’s novel of the same name. Indeed, scores of pulp writers made the transitions into other media such as the slicks, radio plays, and Hollywood, and thrived.

Above all, pulp fiction is fun.

Please give us your valuable comment