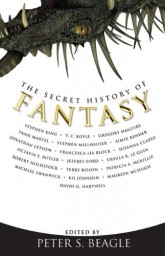

If you go to Tachyon Publications website, this blurb is at the web page for The Secret History of Fantasy:

Fantasy is more than just sword-and-sorcery novels of epic adventures. Here are innovative tales where mythology, fairy tales, and archetypes are re-imagined into a new style of storytelling.

This header is present at the Tachyon website:

“Tachyon – Saving the World One Good Book at a Time.

Tachyon is an independent publisher of smart science fiction and fantasy.”

A few years back when Border’s Books was going under and had a fire sale to eliminate everything. I took some time to look through the science fiction and fantasy anthology section. I noticed a book entitled The Secret History of Fantasy edited by Peter S. Beagle and published by Tachyon Publications. Reading through the introduction by Beagle, I came across this passage:

A few years back when Border’s Books was going under and had a fire sale to eliminate everything. I took some time to look through the science fiction and fantasy anthology section. I noticed a book entitled The Secret History of Fantasy edited by Peter S. Beagle and published by Tachyon Publications. Reading through the introduction by Beagle, I came across this passage:

“I can still recall being in Forbidden Planet, the well-known New York City science-fiction bookstore, with my best friend in the late 1980s, peering dazedly down rows of unfamiliar paperbacks, most with mock-Frazetta covers featuring muscular bare-chested northern-barbarians types rescuing similarly muscular barechested damsels from assorted monsters, and hearing my friend whisper in utter bewilderment, ‘Peter, who are these people?’ I couldn’t tell him.”

I remember the late 1980s. What I think of as “sword-and-sorcery” fiction had died out in mass market paperback in 1985 as I wrote a few weeks back. There were a few sword-and-sorcery novels from Avon in the late 80s by Michael D. Weaver and Paul Edwin Zimmer & John de Cles. What I do remember are the many titles of Tolkien imitation with Darrell K. Sweet covers. I call this “corporate fantasy.” About the only barbarian covers at the time were the Tor Conan pastiches with covers by Ken Kelly. The Tor Conan pastiches were a part of fantasy publishing but were not by any stretch of the imagination the dominant force in publishing.

One of a few things is going on here. Beagle is either wrong by a decade mistaking the late 1970s for the late 1980s. Or he is grossly distorting what actually happened calling the corporate fantasy trilogies “sword and sorcery.”

The central point of Beagle’s introduction is argument against “genrefication.” That is fantasy stories as explicitly within a “fantasy” category.

The contents of the book itself are made up of short fiction that could be described as “slipstream fantasy.” That is mainstream fiction with a hint or dash of the fantastic. Sources include Redbook, Harper’s, The New Yorker, but mostly from genre anthologies and magazines. Tachyon has a companion Secret History of Science Fiction that has a fair number of the same contributors.

“Ancestor Money” by Maureen F. McHugh

“Scarecrow” by Gregory Maguire

“Lady of the Skulls” by Patricia A. McKillip

“We Are Norsemen” by T. C. Boyle

“The Barnum Museum” by Steven Millhauser

“Mrs. Todd’s Shortcut” by Stephen King

“Bears Discover Fire” by Terry Bisson

“Bones” by Francesca Lia Block

“Snow, Glass, Apples” by Neil Gaiman

“Fruit and Words” by Aimee Bender

“The Empire of Ice Cream” by Jeffrey Ford

“The Edge of the World” by Michael Swanwick

“Super Goat Man” Jonathan Lethem

“John Uskglass and the Cumbrian Charcoal Burner” by Susanna Clarke

“The Book of Martha” by Octavia E. Butler

“The Vita Æterna Mirror Company” by Yann Martel

“Sleight of Hand” by Peter S. Beagle

“Mythago Wood” by Robert Holdstock

“26 Monkeys, Also the Abyss” by Kij Johnson

I am not convinced of the superiority of fantasy fiction with a modern setting. A good amount of it is what I call “smirk fantasy.” The set up is to make fun of fantastic things from a modern viewpoint. The type of story goes back to Stephen Vincent Benet’s “The Devil and Daniel Webster” to Thorne Smith’s Topper, L. Sprague de Camp’s “Willy Newbury,” and much of the urban fantasy of today. I am amazed at the lack of wonder, confusion, and disorientation that a modern character would experience if presented with a supernatural situation. All too often the character experiencing the fantastic is reduced to Darren Stephens from Bewitched.

One great story included in this anthology is Robert Holdstock’s “Mythago Wood.” Holdstock was a writer with interesting and often great ideas though sometimes understated execution.

The Secret History of Fantasy includes two essays, “The Critics, the Monsters, and the Fantasists” by Ursula K. LeGuin and “The Making of the American Fantasy Genre” by David Hartwell. LeGuin’s essay is quite good I thought. I liked it enough to find it online and download. The crux of her essay is the obsession of critics/academics with realist/modernist mindset.

David Harwell’s essay is a pocket history of fantasy publishing. Hartwell mentions “consternation” at the success of the Lancer Conan books. He has bigger problems with Terry Brooks’ The Sword of Shannara and subsequent corporate fantasy books. From a business stand point, Lester and Judy Lynn del Rey’s publishing of Brooks was a stroke of genius. They were giving what the reading public wanted.

Hartwell is a strange case to me. He edited a book called The Space Opera Renaissance that contains an excellent introduction and history of adventure science fiction. Hartwell published Jack Vance and Clark Ashton Smith when editor of the Timescape series. He will describe Leigh Brackett as “well written” but views Robert E. Howard with consternation. This is a case of missing the forest for the trees.

Is this a case of Beagle simply cheerleading what they think we should be reading? Or is he a self-righteous and self-appointed would be gatekeeper?

I think Hartwell is more against commoditization of the fantasy genre and the race to the lowest common denominator. I have not read any of his Year’s Best Fantasy anthologies. A look at the contents online does not contain the depths of The Mammoth Book of Warriors and Wizardy.

The question is: to who does fantasy belong? There is a history of imaginative tales in the English language. With Beowulf (in Old English), we have Grendel and a dragon. The Canterbury Tales (Middle English) has “The Tale of Sir Thopas” with a knight on a quest to find his elf-queen. Sir Thomas Malory wrote Le Morte d’Arthur in the mid-15th Century at the transition of Middle English into “modern” English. Let us not forget Shakespeare’s witches in MacBeth or the fantasy A Midsummer’s Night Dream. Epic fantasy/heroic fantasy/sword and sorcery is in the DNA of the language we speak.

These critics are hostile to stories with imaginary settings, an upfront masculinity, and plebian origins of entertainment first in pulp magazines and then mass-market paperbacks. There is a sense of outrage at mere existence of sword-and-sorcery fiction. The idea that sword and sorcery fiction is preventing “literary” fantasy from being published is a straw man argument.

I have no problem if slipstream or urban fantasy is published. Let the market decide what people want to read. My guess is the content of The Secret History of Fantasy was read by a small number of people. This secret history will no doubt remain a secret.

“Epic fantasy/heroic fantasy/sword and sorcery is in the DNA of the language we speak.”

Yes!

Mrs. Todd’s Shortcut is fairly memorable and owes more to Lovecraft than to slipstream. Weird Fiction doesn’t have a home, though, not anymore, even though I actually believe it is at the core of the three wings of Science Fiction (SF, Fantasy and Horror). A lot of those others listed – at least the ones I remember – are definitely slipstream – a genre I can only describe as generally timid. Borges without the wild. Joyce Carol Oates without the realism. Something in-between and usually irritating because of it.

Beagle, on the other hand, likely has never seen where he belongs, because a key thing about his best work is that the work is alien and unbelonging.

-

Today’s slipstream stories are meek. They are the sort of stories that would have been in THE SATURDAY EVENING POST decades ago. The Marvin Kaye era of WEIRD TALES is proving to be a disaster with years between issues (or so it seems).

“The Sword of Shannara”

i tried to read it. Three times. If i ever read the phrase, “the small party” ever again, i will burn (or delete, as appropriate) the book immediately.

i liked his kingdom-for-sale bit, but Shannara has got to be the most repetitive prose i’ve ever read in any genre.

As you write, though: “They were giving what the reading public wanted.” That’s why R.E.H. spent so much time writing westerns – that’s what paid the rent.

-

I recall trying to read Sword of Shanara too. Gave it up as some sort of mopey version of Tolkien. I tried Lord Foul’s Bane too, which was just a colossal mope-fest without any redeeming features. I have nothing against a bit of mopery, but it’s not a thing to be abused.

To put it another way, Moorcock’s Elric did a lot of moping, but he never let it get in the way of reaping blood and souls for Arioch. And he could get it done in 12,000 words or less.

“Is this a case of Beagle simply cheerleading what they think we should be reading? Or is he a self-righteous and self-appointed would be gatekeeper?”

Yes and yes. And I’m a fan of Beagle. ‘Giant Bones’, his book of short stories that takes place in the same world as ‘The Innkeeper’s Song’, is one of my favorite books. I’ve read it numerous times and go back to it frequently.

That being said, given some of the essays that I have read penned by Beagle, I would say that he’s definitely a gatekeeper. A shame.