We might argue about whether Donald A Wollheim is the most significant figure in 20th Century science fiction[1] but there can be little doubt about the influence he had on the development of modern science fiction and fantasy[2] is both broad and deep.

We might argue about whether Donald A Wollheim is the most significant figure in 20th Century science fiction[1] but there can be little doubt about the influence he had on the development of modern science fiction and fantasy[2] is both broad and deep.

He leapt onto the stage early as an ardent fan, and immediately began to shape history: from his proposal for what is arguably the first science fiction convention,[3] through his championing of the fanzine platform via newly-affordable home-printing technologies,[4] and into his uncanny understanding of the potential of rapidly cheapening media such as the pulps and pocketbooks as a platform to make SFF grow[5], his contributions to building the SFF publishing world we know today were enormous.[6]

But where I think Wollheim’s most interesting influence really shows is in his editorial hand.

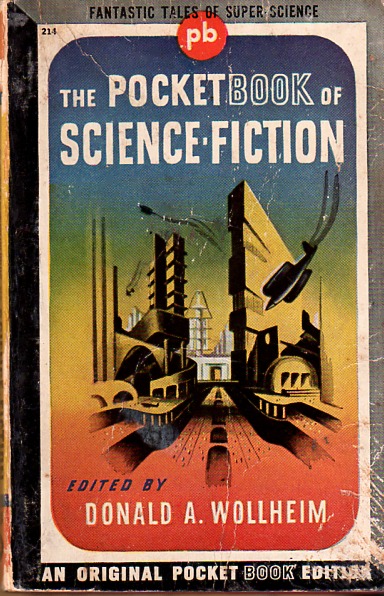

In 1940 the twenty-six year-old Wollheim approached Abling Publications with a proposal to add science fiction to their line-up of western and detective magazines. After two years struggling to keep Cosmic Stories and Stirring Science Stories Wollheim jumped into the book publishing pond early with his Pocket Book of Science Fiction which he edited for Pocket Books (obviously) to publish in 1943. He followed up in quick succession with the Viking omnibus Portable Novels of Science in 1945, which appears to be the first effort at an SFF anthology by a major publisher – and consequently the first such anthology in hard-back.

Both of these collections include impressive works, such as Olaf Stapledon’s Odd John[7] and Stephen Vincent Benét’s By the Waters of Babylon[8] as well as a few “duds” that may have been impressive at the time, but for various reasons haven’t aged very well.[9]

But the pump was primed, and Wollheim went from here into what I think was his biggest contribution to genre: editor of original anthologies (something of an innovation at the time) and from there into publishing what is possibly the greatest series of fiction anthologies of all time: World’s Best Science Fiction.

As I’m sure everyone reading this is already aware, Wollheim launched this series in 1965 with a truly impressive line-up that includes Ben Bova (Men of Good Will), John Brunner (The Last Lonely Man), Philip K. Dick (Oh, to Be a Blobel!), and Fritz Leiber (When the Change-Winds Blow). It even – in deference to its title I presume – includes work in translation from Josef Nesvadba (Vampires Ltd. – trans of his original Czech story Upir ltd) and Harry Mulisch (What Happened to Sergeant Masuro? – trans from the original German). This collection spans an enormous range, not only in the nature of the stories themselves – which is itself impressive – but in terms of the “tone” of the voices. This is no monolithic tome, but a thick slice of what the SFF world was reading.

This approach to SFF seems to have served Wollheim well as he moved forward with later editions of the anthology – the 1967 edition contained work from writers as different as Moorcock, PKD, Pohl, and Zelazny – and showed in his selections for inclusion in the late 60s and early 70s editions of his SFF line of Ace Doubles, with Andre Norton, Jack Vance, Samuel Delaney, Marion Zimmer Bradley, Dean Koonz, and Robert Silverberg all sharing the stage.

Unsurprisingly, many of these names also figure in the World’s Best anthologies of 1968 and 1970 – along with greats like Larry Niven (Death By Ecstasy – 1970, Handicap– 1968), Ursula le Guin (Nine Lives – 1970), and Norman Spinrad (The Big Flash – 1969).

This remarkable range of voice (and politics) is a common thread through his editorship at DAW and through the whole series of World’s Best to the last volumes: Even in 1989 we can read Kristine Rusch (Skin Deep) and John Shirley (Shaman) alongside Fred Pohl (Waiting for the Olympians) and David Brin (The Giving Plague), and in the last volume published in 1990 we get options like Orson Scott Card’s Dogwalker and Robert Silverberg’s Chiprunner alongside J.G. Ballard’s Warfever and Brian Aldiss’s North of the Abyss.

But Wollheim’s contribution here is not simply in being good at picking stories – and pick them he did – or even in being willing to pick amazing stories without concern for whether they were to his personal taste.

No, the key lesson we can take goes much deeper.

Donald Wollheim worked seeing the amazing in stories, and in writers. You can see from the contents pages of his anthologies that he chose stories on the skill of the author, and on that seed of amazing that makes the best SFF, no matter what your personal taste is. He disagreed with many of the trends of the New Wave, for example, and yet he regularly included the best work of its disciples in his anthologies – because they were amazing stories, even if they weren’t quite in his well house. He was praised by authors for his dedication to helping them succeed – both by being a strict editor and by being an enthusiastic coach and cheerleader.

And as an editor, he reportedly didn’t try to impose his vision on the writer as John Campbell was reputed to do[10] – instead he worked on helping authors find their own vision, and to project it onto the page in the most amazing way possible.

Sadly, this kind of dedication to the field of SFF is lacking in the modern era. We need more people to “be Wollheim” and fewer being Knights and Campbells and Ellisons. There’s probably a place for those latter editors in the world, and certainly I’ve seen some very interesting anthologies and magazines come through the gates they keep.

But what we need is a giant like Wollheim who cleaves fast to the Law that should be engraved on every SFF editor’s desk:

Find the Amazing. Look everywhere. Make it grow.

[1] I’ll win.

[2] Some claim Wollheim singlehandedly

[3] The infamous road-trip of October 1936 – see Fred Pohl’s account of the event.

[4] Wollheim was a founder and enthusiastic participant in FAPA, which is arguably the longest-running “high volume” (for measures of volume that acknowledge the limitations of the medium and the niche nature of the material) amateur press association in the world.

[5] Personally, I think he would have been a rabid proponent of both indie and tradpub ebook platforms.

[6] Indeed, I would argue that while naming Gernsback to the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame as the first editor and publisher in 1996, really Wollheim’s contribution and influence far eclipses that of Campbell and it’s a real shame Wollheim wasn’t honored by induction until 2002.

[7] Progenitor of a raft of later novels and stories about what happens when humanity evolves and the “superior form” regards the mass of humanity as beneath them – arguably an early iteration of the concepts that lead to both Bradbury’s musings on the subject and the X-Men, but more importantly an example of message fiction done right if you pay attention to historical context. Read Galaxy’s printing of the story here.

[8] An early post-apocalyptic tale that I think has aged very well – read it here.

[9] One example is Before the Dawn by Professor Temple Bell, writing under his pseudonym John Taine. The story is an impressive piece of technological speculation rooted in real science of the day (and coincidentally gives us perhaps the first example of a “time telescope” for looking into the past) but in modern terms the science stumbles and makes it a bit hard to read now. See the original here – note who published the story in book form, and the commentary in the forward. So much for SFF “always having been for children”.

[10] Admittedly, a bigger pressure for this sort of thing when you’re trying to keep a commercial magazine afloat.

“He leapt onto the stage early as an ardent fan, and immediately began to shape history…”

His fanzine, The Phantagraph, is a landmark. How many other fanzine editors could make the claim that they published HPL, REH and Clark Ashton Smith while all three were still alive? That also points up the fact that Wollheim was a major force in fantasy, not just SF, for 50yrs. In the US, he’s the one who broke out LotR. He’s the one who got Witch World, Elric and Imaro out there in front of the public. He published QUAG KEEP.

http://howardworks.com/PhantagraphV4N3.html

-

It’s true – he focused more on what normally gets classed as science fiction in the 40s and 50s but he was definitely spanning the field. HPL was also included in his first Pocket Book anthology so yes, it goes right back to the beginning – I’ve so far been unsuccessful finding anything other than Ackerman’s account, which only gives us 2 fan names, but I wouldn’t be surprised to find Wollheim among those fans who visited Merritt at his office the day after the first Worldcon. On the other hand, by Ackerman’s account his first encounter with the NY fans during that trip was to be punched in the gut by Kornblum so maybe not…

-

“It’s true – he focused more on what normally gets classed as science fiction in the 40s and 50s but he was definitely spanning the field.”

When Wollheim was at Avon, he arguably published more fantasy — in both paperbacks and digests — than any other US editor during that period, with the possible exception of Derleth. The Avon Fantasy Reader link:

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Avon_Fantasy_Reader

While at Avon, Wollheim published paperbacks devoted to HPL, Merritt and CS Lewis. Keep in mind that the postwar era in America was a wasteland for fantasy/horror. During that period, Wollheim and Derleth tower over all others in that regard.

https://infogalactic.com/info/Donald_A._Wollheim#Wollheim_as_editor_and_publisher

-

Yes, it was a real wasteland – and one of the reasons why Wollheim was so adamant about keeping fantasy on the radar. One cause of the empty shelves was the death of short-form markets that had traditionally catered to “crossover” fiction – ie not strictly “Campbell Crew” type SF. Space opera survived a bit longer because of the “sciencey bits” but fantastic and weird tales started to go into a tailspin because of the grip Campbell’s school was getting on the narrative. Add to this the need to be taken seriously, and you have a recipe for disaster that doesn’t really get upturned until Wollheim’s coup with “bootleg Tolkien”.

Actually, to think of it: Wollheim and Derleth’s commitment to keeping the fantastic side of SFF alive in the 50s and 60s might well be directly responsible for the fantasy role-playing game boom of the 70s!!! (though the category made a fairly successful shift into film in the same period, so maybe I’m going too far).

-

“Wollheim and Derleth’s commitment to keeping the fantastic side of SFF alive in the 50s and 60s might well be directly responsible for the fantasy role-playing game boom of the 70s!!!”

Just do the math on Appendix N:

http://www.digital-eel.com/blog/ADnD_reading_list.htm

By my rough reckoning, Wollheim published — either at Avon, Ace or DAW — about 75% of the authors listed by Gygax. Who knew that Gary was also a tool of the Kremlin?

-

Suddenly that Red Box seems…different somehow!

No, you’re absolutely right. It was DAW and Avon and Ace keeping the lamp lit, and Wollheim was at the helm at all three at one point or another through the 50s, 60s, and 70s. He even successfully talked several publishers into *starting* SFF lines (into which he injected fantasy) even when they had previously not considered it.

Of course, Wollheim also prevented the clean death of the Gor series after Ballantine dropped it when they were acquired by Random House. So perhaps his hands aren’t so clean after all.

-

-

-

“I’ve so far been unsuccessful finding anything other than Ackerman’s account…”

We know Wollheim was a Merritt fan, but I would bet he wasn’t there with that group. He had been in correspondence with Merritt and he lived in NYC. I would guess that Don had already visited The American Weekly. Merritt was known to be friendly and accommodating with fans.

An interesting question.

-

You may be right. First: Ackerman’s account suggests not the best relationship with the “teen division” of NY fandom on his first encounterbwith Wollheim in 39. Seems unlikely their relationship mended so quickly, though Ackerman’s account says he was mortified by the idea of fans being barred from the Con so perhaps that went a way to mending bridges. However, I would expect Ackerman’s group to have included people like Bradbury and Bok, possibly fans from the Chicago cluster. People 19 or older from far from NY. Wollheim as you say had plenty of other opportunities to meet Merritt.

-

“He was praised by authors for his dedication to helping them succeed – both by being a strict editor and by being an enthusiastic coach and cheerleader.”

You see this admiration and trust from his writers again and again. Look at how many of the authors he developed followed him from Ace to DAW. Pournelle, Dickson, Stableford, Tubb, Brunner, Aldiss, PK Dick…and Andre Norton:

“When Don told me he was leaving Ace Books, I had a book ready for him (Lore of the Witch World). I said that he could take it with him and that I’d go too, since I wasn’t under a contract. He was a nice person to work for..”

Wollheim evoked a great deal of loyalty from his stable of authors. Not bad for the KGB’s prime operative in the SFF publishing field.

Le Guin referred to him as a tough editor who made her better. (Forget the exact wording). And from early on in his feud with Gernsback Wollheim showed his stripes: he knew the *writers* are the thing and need to be treated fairly.

The “accusation” of communism is an interesting one though. Quite apart from the fact he obviously changed over a lifetime and was really quite conservative by the 60s I think it’s actually questionable how “communist” he really was in the beginning. Now Michel was definitely a fellow traveller, and I don’t think there’s any doubt DAW was sympathetic to the socialist and anarchist movements of the day. But we have to remember that this is an era when leftist movements were fighting for democracy in Spain and protesting Hitler, and before the real ugliness of the USSR was known. The true extent of the Great Purge and the gulags wasn’t really well known in the West until much later than the the Futurian manifesto, and even when it was there were plenty of persuasive apologists who argued that Stalinism and Leninism weren’t true socialism.

We also have to remember that Wollheim was 21 in 1939 – and he was the old man of NY fandom.

No, I think really he was more of a techno-utopian who was attracted to some of the promises of socialism at the time, that he was initially enthusiastic about the idea of SFF as a vehicle for change (an idea cribbed from Gernsback), but that he grew into a philosophy where amazing visions of the future and other worlds would *inspire* the future, rather than the message fiction approach. By the time he was driving Ace’s SF line he was all about the story, that much is clear.

We need more like Wollheim these days.

-

We do. And actually I think we do still have some Wollheims out there: people who see the awesome in new authors and work to build them up, people who work to build new venues and champion new publications, people who just love great stories and want to see more. What we need is for those people to also take advantage of how *easy* it is now for us to publish and take a stab. Your effort may sink, it may float, it may be a rocket to the stars. But every effort moves us toward a more diverse, more exciting realm of L-space.

‘The “accusation” of communism is an interesting one though. Quite apart from the fact he obviously changed over a lifetime and was really quite conservative by the 60s I think it’s actually questionable how “communist” he really was in the beginning. (…) I think really he was more of a techno-utopian who was attracted to some of the promises of socialism at the time…’

My thinking is along the same lines, Kevin. This suddenly-arisen false narrative of “Donnie the Commie” — as in “Once a commie, always a commie” and Wollheim died a commie — just doesn’t hold up to even the most cursory scrutiny.

Let me put it this way… Heinlein, Philip K. Dick and Pournelle all started out as socialists/commies and later went Libertarian or Right. Poul Anderson admitted he went through a major globalist phase after WWII — read his “UN-Man” stories. “Pournelle a commie?!?” you say?

http://voxday.blogspot.com/2017/09/jerry-pournelle-week-iii.html

If Pournelle — the son of a Navy commander — could consider himself a communist in his 20s AFTER fighting commies in Korea and attending West Point, then how can we judge Wollheim at all? He more than made up for his youthful indiscretions.

It would behoove the PulpRevvers pushing this false narrative and low-info with-hunt to consider the precedent they’re setting. If Wollheim — who spent much of his 40+yrs after the Futurians nurturing and publishing (generally) superversive, pulpish fiction — can be exhumed and spat upon, what message does this send writers not yet in the fold?

If some author who attended Occupy Wall Street but has now seen the Light — believe me, it does happen — looks at what’s happening with Wollheim, what incentive does he have to join the PulpRev? What middle-of-the-roader with even a modicum of knowledge about Wollheim’s place in SFF history will want to come near the movement? Who wants to join the ranks of low-info witch-hunters? Obviously, if you screw up ONCE you’re on the blacklist forever, no matter how much REH, ERB, Merritt, CS Lewis, CL Moore, Leiber, Anderson, Norton, Tubb, Carter, Dickson etc that you publish subsequently. Then again, Don did nurture and publish the works of his fellow commie, the insidious Dr. Jerry Pournelle. Case closed!

So when does the video throwing Heinlein, Anderson, PKD and Pournelle under the bus come out? I can’t wait.