WRIGHT ON Lost Works – The Worm Ouroboros

Tuesday , 28, February 2017 Appendix N, Before the Big Three 33 CommentsThe Worm Ouroboros

Back in the day, ere ever Appendix N was penned by Gary Gygax, the lover of works of fantastic fiction was starved. Paper shortages in World War Two had killed off magazines catering to weird tales of oriental splendor, monsters and wizards and deeds of derring-do, and older books venturing into the Perilous Realm were out of print. There were children’s books by L. Frank Baum, or E. Nesbitt, or Lloyd Alexander, and there were medieval and ancient works by Mallory or Homer to slake one’s thirst, but little else.

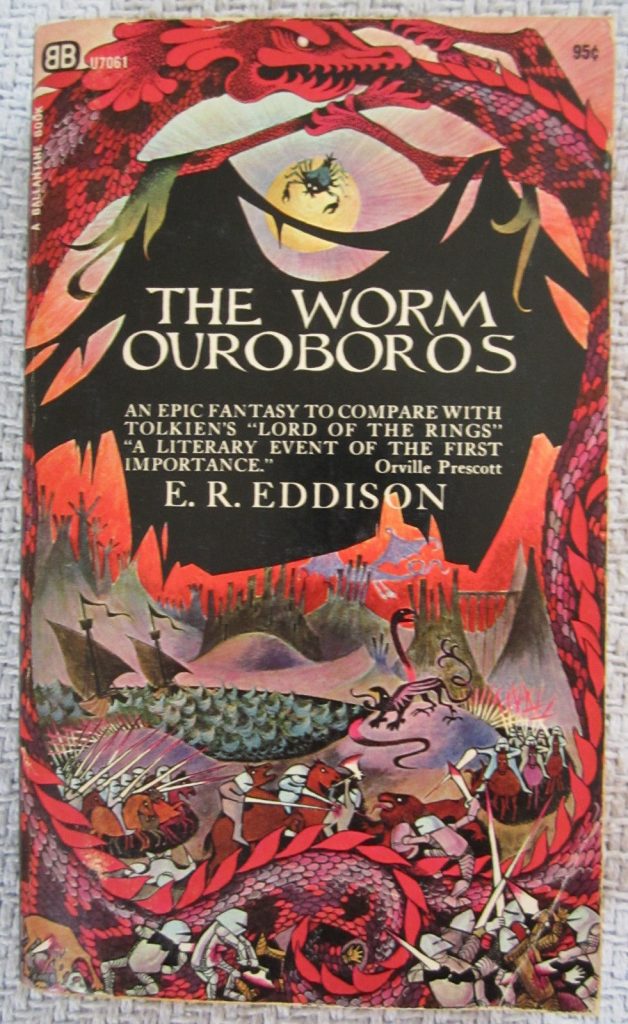

After Tolkien astonished and confounded the world with the unexpected success of Lord of the Rings, Ballantine Books in 1969 launched an imprint meant to revive this older fantastic fiction, including weird tales from the pulps or unique literary visions from England, largely lost and forgotten, together with anthologies of new works. It was placed under the hand of Lin Carter. In 1974, after the company was sold to Random House, the line was dropped.

It was called the Adult Fantasy Series, tellingly enough, not because it contained salacious material, but because fantasy books not aimed at children were so rare. In those days Ursula K LeGuin’s A Wizard of Earthsea (1968) was shelved next to Andrew Lang’s many-colored Fairy Books.

That these tales have become lost again, and a whole generation has let their memory fade once more, is an ironic testament to the need of lovers of literature to battle both against entropy and against the fashionable disdain of the elite.

The common man throughout the ages reliably admires and preserves those things that pass the test of time and last for ages. The elite craves novelty. The elite has neither loyalty to their fathers nor to their posterity, and will not preserve the legacy from one, nor pass it to the other. Snobs of earlier generations could be relied upon at least to preserve snobbish literature like Shakespeare, coarse jokes for the groundlings and all.

* * * *

Before even the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series proper hit the shelves, were certain precursor books. These are the books that had the unicorn logo of the series on their reprints, but not on the original printing.

Only five authors are included in this august set: J.R.R. Tolkien himself, whose work looms like a mountain over the whole of modern fantasy, E.R. Eddison, who was akin to Tolkien in scope, if opposite in theme; Mervyn Peake, who was akin to Tolkien in no way, except length; David Lindsay and Peter S. Beagle.

Each of these authors has the one distinction which no author after shares, except, perhaps, for Cordwainer Smith. They are such pioneers that there is no work to which their work can be likened.

We tend to think of Tolkien as firmly in the center of the fantasy genre only because the fantasy genre took so much impetus and inspiration from him. But at the time he wrote, there were no authors like him, except possibly for these authors who, paradoxically, were nothing like him.

The drawback of being unlike any other author is that your work becomes an acquired taste. The author is alone in the wilderness, without the crutch of having other books the reader also likes act as an introduction to yours.

* * *

THE WORM OUROBOROS by E.R. Eddison is a book entirely sui generis. It is not a reprint from Weird Tales, but is a unique literary vision from England, dating from 1922.

It is shelved with fantasy novels, but it has as much in common with Shakespeare and the Iliad as it has with William Morris. (If you do not recognize his name, fret not. He is the man who invented the fantasy genre. When I write a review of WOOD BEYOND THE WORLD, I will mention his accomplishments.)

The most striking thing about OUROBOROS is the language.

It is a fanfare of the gods whose spirits wax high-flown on ambrosia and soma, a crash of mystic cymbals, and a drumbeat of ambitious giants storming Olympus. It is a very delirium of prose, as richly crusted thick with gems of words as the gnarled shell of a Kraken seen at sea, and mistaken by an unwary Hibernian sailor for the outpost of some golden isle.

In a genre often plagued with forsoothery and faux-archaic speech, it is a wonder to read an author who can pen an entire novel in Elizabethan English without a false step.

But be warned: this is like hearing a classical symphony after a hearing nothing but jazz, rock, and dance music. It is almost not English, but a language older, richer, more elfin yet more gigantic, and as dignified as a king in full regalia leading a pavane, not merely of noblemen and gracious ladies, but demigods in all their splendors.

The plot concerns two great nations on a world afar, where the cruel and magnificent King Gorice, at the celebration of the anniversary of the nativity of the noble and magnanimous Lord Juss, sends a loathsome Ambassador to demand his humiliating submission and fealty.

Lord Juss offers to settle possession of his island kingdom by a wrestling match between Gorice and the brother to Juss, the herculean Lord Goldry Bluszco. Omens surround the dire event; Gorice employs foul tricks and ignoble sleights, while his men cow the hapless judge of the match; Goldry Bluszco in wrath shatters the skullbone and spine of the undefeated king. His men spirit the body away in secret, departing by night, but when they return to the Iron Tower of Carce, Gorice is alive again in another body: for Gorice is immortal.

As great in the arts of grammary and witchcraft as his predecessor was in wrestling, Gorice summons up an unclean spirit from the abyss, and sends it against the ship of Lord Juss and his brethren. Goldry Bluszco is snatched away amid a stench of sulfur and gusts of horrid laughter. Juss and his two heroic cousins are overcome with rashness akin to madness and make a doomed assault on the Iron Tower; are defeated yet escape with their lives. Lord Juss learns in a dream his brother’s location, and he vows a mighty vow to seek the far-fabled and enchanted mountain beyond all civilized lands, Koshtra Belorn, accursed and fated never to be climbed save by one who has looked upon it from above. And there is only one mountain taller still, and looks down upon the haunted peak.

And this is just the opening scenes.

There are sword-fights and sea-fights, brave falcons and women fair beyond words, feast halls and far campaigns, sieges, quests, mountains scaled, monsters slain, bold words, rash oaths, great deeds, and the fauns are seen to dance by moonlight in the woods.

It is usual for a review to warn readers of flaws in the work, that they not be surprised by any shell fragments found in the chowder. I cannot serve this office, because, while I know what others critiques have listed as faults, I confess I do not see them. But I can list them.

For one thing, the book has no end. Literally. It does not break off in a fragment, but it ends on a note that makes something of a mockery of all that has gone before. All the hard won gains of victory are wished away with a magic wish, and Ouroboros eats its own tail in truth.

The second flaw is related to the first. Mr. Eddison has a remarkably romanticized view of war, so much so that his heroes prefer war to peace, and eagerly forswear it for a chance to trap themselves and all their people in an endless Valhalla, a paradise of war. As if Meriadoc Brandybuck were to yearn to return to the Battle of the Pelannor fields, eager to see the Theoden perish again beneath the mace of the Witch-King of Angmar, merely for the glory of drawing his knife in the face overwhelming peril once more.

For a man writing after World War One, this theme may strike the modern reader as repugnant. However, Mr. Eddison was writing not for modern men, but in homage to longdead pagan demigods like Achilles and Ajax, and mighty Hector.

On the other hand, the essential melancholy of paganism is missing from this work, so the reader should not expect anything more profound than a glorification of warfare and the warrior ethic. This is a flaw only in the sense that comic books and pulps are flawed. A work meant to have no deeper meaning is not flawed when it is seen to have no deeper meaning.

Third, some critics wag their heads at how much more character and personality the black-hearted villains have than the high-hearted heroes. For their taste, flawless goodness and heroism are drawbacks.

Here, both heroes and villains here are larger than life. The villains are treacherous, or lustful, or drunks, or vain, and at least one of them traffics with hellish powers with tragic result. But any who say that the wrathful Spitfire, and dandified but deadly Brandoch Daha, or the strong-thewed Goldry lack character and depth merely suffer a personal blindness. There is a certain kind of reviewer who reads PARADISE LOST and thinks Lucifer in his boastful wretchedness is the hero.

A fourth point is the use of names, selected indifferently from various nations, or pure imagination, with more exuberance than sense. For example, the kin of Goldry Bluszco are named Spitfire and Brandoch Daha. The first has a distinctively Slavic spelling, the next is English, and the third sounds vaguely Celtic.

The names of the nations and races are taken directly from nursery tales, but none of the persons involved in the least resemble their namesakes, save that the Demons from Demonland have horns on their heads (which are mentioned in Chapter One and never again). So we are introduced to Witches, Imps, Pixies, Goblins and Ghouls, none of which has the least connection with anything those words suggest to the reader: all are tall and stalwart men or strikingly beautiful women. The Demons, by the way, are the good guys.

Some readers find this too distracting to overcome. Contrariwise, I find it is no worse than Tolkien using the word ‘elf’ to refer to beings much taller and fairer than Robin Goodfellow from Shakespeare or Hermey the Dentist from Rakin & Bass.

And, unlike the less jarring place-names used by E.R. Eddison in his other books, I have no trouble remembering these.

Again, the action is set on Mercury, which is visited in a dream by a man named Lessingham, who flies thither on a winged chariot pulled by a hippogriff. This so called Mercury has the trees and beasts and birds of Earth, and Earth’s moon shines on it, and classical gods from Olympus rule here, as well as beasts merely fabled on Earth dwell here, such as the cockatrice or hippogriff.

Contrariwise, I assume this is this is alchemical version of Mercury, the land of the pagan god of magic, and is no more like the scientific view of Mercury than Lord Juss is like a Demon.

Some readers are annoyed that the scene and setting are introduced by Lessingham, who, in a prolog, enters the chamber of his English manor house in Wastdale set aside for dreaming dreams beyond the earthly sphere. He is forgotten after the opening lines of Chapter Two, and so the framing story has no closing.

Contrariwise, I am not distracted by this conceit any more than a prologue where Edgar Rice Burroughs explains how he came into the possession of a manuscript written on Mars by his uncle John Carter. In those far off days, fantasy was as rare as a hippogriff, and the audience often needed to inch into the shallow end until they got used to the water.

But I have heard these criticism often enough (they are mentioned by nearly every critic) I thought it fair to give a warning to readers whose palates are more sensitive than mine.

My final warning is also my strongest recommendation. If your tastes are like mine, if you cherish prose that rings like poetry, prose that holds the gleam of gems, and softness of women, and ferocity of falcons and the clash of noble swords ringing like thunder, this book is for you. If high language and archaic turns of phrase leave you nonplussed or irked or throw you off the steed of the story, wait until after you’ve read Milton or Keats and want more.

If you cannot stomach the rich repast of a two page description of the decorations of the palace of the lords of Galing, intricate as the crust of a Faberge egg, including the names of monstrously huge precious and semi-precious stones from whose single gems their thrones are carven, and their different hues by night and day, including the figures on the flagstones, the jewels inset into the cracks and veins of the colored marbles, and the fabled beasts of whom the capitals of their columns are carved, then this may not be for you.

Because then the arms, accoutrements, gems, belts, buskins, coronets of the warlike heroes will be described for another page or so, and when they open their mouths, the ringing majesty of each ornate phrase, heavy with Homeric metaphors, is meet for those who dwell in such presence chambers and wear such lavish richness.

I yield to the temptation of quoting a single passage:

Like a black eagle surveying earth from some high mountain the King passed by in his majesty. His byrny was of black chain mail, its collar, sleeves, and skirt edged with plates of dull gold set with hyacinths and black opals. His hose were black, cross-gartered with bands of sealskin trimmed with diamonds. On his left thumb was his great signet ring fashioned in gold in the semblance of the worm Ouroboros that eateth his own tail: the bezel of the ring the head of the worm, made of a peach-coloured ruby of the bigness of a sparrow’s egg. His cloak was woven of the skins of black cobras stitched together with gold wire, its lining of black silk sprinkled with dust of gold. The iron crown of Witchland weighed on his brow, the claws of the crab erect like horns; and the sheen of its jewels was many-coloured like the rays of Sirius on a clear night of frost and wind at Yule-tide.

As I feared, like a bibber who sucks too sweet a nectar, I am grown drunk with words, and must have more.

Here is a trifle of dialog, selected at random, were the villainous and foppish Corund sups with Prince LaFireez, but seeks to hide the fact that a friend and ally of LaFireez is even then chained below in this same castle where they sit: a recent assault (during which the friend was captured) is blamed on another and weaker prince named Gaslark. With them is the Lady Prezmyra, who is described thus ” Tall was that lady and slender, and beauty dwelt in her as the sunshine dwells in the red floor and gray-green trunks of a beech wood in early spring.”

La Fireez said, “Strange it is that he should so attack you. An enemy might smell some cause behind it.”

“Our greatness,” said Corinius, looking haughtily at him, “is a lamp whereat other moths than he have been burnt. I count it no strange matter at all.”

Prezmyra said, “Strange indeed, were it any but Gaslark. But sure with him no wild sudden fancy were too light but it should chariot him like thistle-down to storm heaven itself.”

“A bubble of the air, madam: all fine colours without and empty wind within. I have known other such,” said Corinius, still resting his gaze with studied insolence on the Prince.

Prezmyra’s eye danced. “O my Lord Corinius,” said she, “change first thine own fashion, I pray thee, ere thou convince gay attire of inward folly, lest beholding thee we misdoubt thy precept–or thy wisdom.”

Corinius drank his cup to the drains and laughed. Somewhat reddened was his insolent handsome face about the cheeks and shaven jowl, for surely was none in that hall more richly apparelled than he.

Now it is too late. I cannot stop.

“There’s little sword-room,” said Juss. And again he looked forth eastward and upward along the cliff.

Brandoch Daha looked over his shoulder. Mivarsh took his bow and set an arrow on the string.

“It hath scented us down the wind,” said Brandoch Daha.

Small time was there to ponder. Swinging from hold to hold across the dizzy precipice, as an ape swingeth from bough to bough, the beast drew near. The shape of it was as a lion, but bigger and taller, the colour a dull red, and it had prickles lancing out behind, as of a porcupine; its face a man’s face, if aught so hideous might be conceived of human kind, with staring eyeballs, low wrinkled brow, elephant ears, some wispy mangy likeness of a lion’s mane, huge bony chaps, brown blood-stained gubber-tushes grinning betwixt bristly lips. Straight for the ledge it made, and as they braced them to receive it, with a great swing heaved a man’s height above them and leaped down upon their ledge from aloft betwixt Juss and Brandoch Daha ere they were well aware of its changed course. Brandoch Daha smote at it a great swashing blow and cut off its scorpion tail; but it clawed Juss’s shoulder, smote down Mivarsh, and charged like a lion upon Brandoch Daha, who, missing his footing on the narrow edge of rock, fell backwards a great fall, clear of the cliff, down to the snow an hundred feet beneath them.

As it craned over, minded to follow and make an end of him, Juss smote it in the hinder parts and on the ham, shearing away the flesh from the thigh bone, and his sword came with a clank against the brazen claws of its foot. So with a horrid bellow it turned on Juss, rearing like a horse; and it was three heads greater than a tall man in stature when it reared aloft, and the breadth of its chest like the chest of a bear. The stench of its breath choked Juss’s mouth and his senses sickened, but he slashed it athwart the belly, a great round-armed blow, cutting open its belly so that the guts fell out. Again he hewed at it, but missed, and his sword came against the rock, and was shivered into pieces. So when that noisome vermin fell forward on him roaring like a thousand lions, Juss grappled with it, running in beneath its body and clasping it and thrusting his arms into its inward parts, to rip out its vitals if so he might. So close he grappled it that it might not reach him with its murthering teeth, but its claws sliced off the flesh from his left knee down ward to the ankle bone, and it fell on him and crushed him on the rock, breaking in the bones of his breast. And Juss, for all his bitter pain and torment, and for all he was well nigh stifled by the sore stink of the creature’s breath and the stink of its blood and puddings blubbering about his face and breast, yet by his great strength wrastled with that fell and filthy man-eater. And ever he thrust his right hand, armed with the hilt and stump of his broken sword, yet deeper into its belly until he searched out its heart and did his will upon it, slicing the heart asunder like a lemon and severing and tearing all the great vessels about the heart until the blood gushed about him like a spring. And like a caterpillar the beast curled up and straightened out in its death spasms, and it rolled and fell from that ledge, a great fall, and lay by Brandoch Daha, the foulest beside the fairest of all earthly beings, reddening the pure snow with its blood. And the spines that grew on the hinder parts of the beast went out and in like the sting of a new-dead wasp that goes out and in continually. It fell not clean to the snow, as by the care of heaven was fallen Brandoch Daha, but smote an edge of rock near the bottom, and that strook out its brains. There it lay in its blood, gaping to the sky.

Now was Juss stretched face downward as one dead, on that giddy edge of rock.

As I said, a book of this type is an acquired taste. It is not meant for everyone. But if it is meant for you, welcome home.

Yes, this is undoubtedly so. Great book that I need to re-read.

For all its flaws, I love this book. It has something no other novel has, whatever that something is. I just reread this about a year ago.

BTW, Eddison was a huge Haggard fan and sent a copy of “Worm” to HRH. Tolkien, Doyle and CS Lewis were also H. Rider Haggard fans. Morris may have invented fantasy, as Carter always claimed, but HRH was astronomically better known and widely admired –SHE being one of the best-selling novels of all time. That’s not counting the other side of the pond where ERB, Merrit, HPL and Robert E. Howard were all admirers.

-

That’s a huge encouragement. I grew up in South Africa, and H Rider Haggard’s stories were more or less the mythology of English-speakers, there. They were regarded as hopelessly Victorian by the baby-boomers (my parents), but as high adventure they’re iconic. Of course, their colonial attitudes to [cough] POC [cough] were unremarkable for their time.

-

Since I finally really “discovered” HRH — after years of thinking ERIC BRIGHTEYES was the only Haggard worth trying to read — I’ve read about 10 of his novels. Most are set in Africa and I have to say that, in quite a few of them, a black character ends up being the most intelligent and courageous person in the tale. There are practically no black protagonists, per se, but excellent supporting characters. Can we say the reverse about anything NK Jemisin has written? No.

IMO, Haggard has nothing to be ashamed of.

-

No, nothing to be ashamed of.

Umslopagaas and Ingosi were very well-rounded characters, and their ‘voices’ were just epic. The cadences ‘sound’ Zulu, such that you know Haggard had heard it spoken.

“Engiwakhulume! I have spoken!”

-

-

The Progressive crowd will hate Haggard, but think of the opening pages of King Solomon’s Mines, and the narrator’s remarks upon “natives” and “gentlemen.”

Or Ignosi’s farewell to his friends and his remarks upon their culture versus his.

That kind of unbiased common-sense could never come out of the Progressive crew today.

I believe Haggard really did “judge based on the contents of a man’s character, not the color of his skin.”

-

Haggard is a Master of Adventure, and has nothing to be ashamed of. His Zulu and Hottentot characters are real people and the real heroes of his stories.

Read the Ivory Child and see how Allan Quatermain reacts to the death of Hans. Or Mameena’s story in Child of Storm. Or Umslopogaas and Galazi in Nada the Lily.

Great stories, well worth reading.

Great review and insight another added to the To Read list.

Especially like drafting Merry Pippin to make a point concerning two approaches to war.

I was taken aback by the ending, it is true, and it does not QUITE satisfy me for the reasons you mention. I would also like to have had some closure to the framing device with Lessingham. But overall, this is an immense and wonderful work, fully worthy to sit beside Tolkien. It shows heroism of a very different sort than the down-to-earth nature of the hobbits of Middle Earth. The back cover of the Dover edition compares it to the Arthurian Legends, and this is accurate. It also took a little time to get used to the fantastical names, but I grew to love them.

-

The ending is the biggest minus for me. Still a classic.

The other big minus for me was the nature of the Impland chapters and the complete lack of foreshadowing there. During this section, our heroes encounter a number of mysteries and enchantments, but these tend to be explained offhandedly either at once or after the fact. Why are the three captains fighting each other on the hills? Oh, the hills are enchanted. Didn’t you know? After killing the manticore, Juss suddenly tells his friend that if they cover themselves in the blood the other manticores will avoid them. Well! Rather abrupt. Information provided on the spot. The mountain can’t be climbed until you look down upon it? I don’t think it is even mentioned until they are already there…

But these aren’t really more than nitpicks. These chapters have much more of the myth-logic, or fairy-tale-logic of legends than the mundane chapters of intrigue and seduction and politics at the Witchland Court. In the end I did enjoy the Witchland segments more. I might have to agree with the people who think the villains are a tad more fleshed out. I wish we got to spend time with the Demon-Lords in less hectic circumstances in order to get to know them, since we already admire and root for them.

If you are going to try to write Epic Fantasy (perhaps any type of Fantasy) in the English language, you need to read this book at least once.

-

Seconded. But I wonder…what books in other languages have people saying the same thing about them, that we don’t know of, we poor souls imprisoned by our mother tongue?

-

Imprisoned?

Nay, say rather that we are UNLEASHED by the power of Shakespeare, Chaucer, Milton, McCauley, Churchill, Dunsany and Tolkien!

If other peoples have such writers, then let them hold their works as high, and we will lead them in a race to glory!

-

Just a heads up: this here Librivox reading is a thing of beauty

https://librivox.org/the-worm-ouroboros-by-e-r-eddison/

-

Me: Sounds amazing, but muh backlog.

Caleb: Librivox, my dude.

Me: That is so perfect, memes fail me.Thank you both!

-

Cool! Thanks, Caleb!

I first tried to read this book when I was in high school and found a copy in the local public library. I think I made it through the first three or four chapters. I tried again in college when that first Ballantine edition came out with much the same results.

I tried again a few years ago and loved the book.

Glad to know about the Librivox recording. I’ll add that to my drive-time listening when I finish with their recording of The Night Land

-

That was very much my experience, Carrington. Could barely get stated the first couple times, The third time, a decade later? BAM! After the first chapter, it’s pretty much non-stop.

My copy has sat for years unread. I pick it up from time to time thinking I’m going to read it next but then it gets put away. A great review and it is now back in my reading order. This is exactly what I need to read next.

That quote is a good ‘un. Howard and Eddison wrote in utterly different styles, but in both cases you can feel sheer energy just leaking out of passages describing gory action, and you can feel that they felt almost ungodly enjoyment while writing them.

Any indications that Howard ever read The Worm Ouroboros? He would’ve appreciated it, in more ways than one.

-

Yeah, there is a bloodthirsty exuberance in TWO that just carries you along. Very much a Homeric or “Red Branch” (Ireland) ethos going on there.

Eddison is one of those writers, like Flaubert, that many people think Howard SHOULD have read, but there’s no evidence for it.

https://web.archive.org/web/20051223144402/http://www.rehupa.com/bookshelf.htm

-

I seem to recall an article in Amra that pretty much clinched that REH had read Salammbô. That was many rears ago; so, I could be mis-remembering.

-

Spraguey pointed out a couple of possible correspondences, but nothing close to “clinching” it. Believe me, I’d be cool with it, but there’s really no evidence. One would think REH would mention it just for the “Look at me, I’m well read” factor. He certainly wasn’t above that, sometimes. Probably the most telling thing is when he was discussing French writers with HPL and only mentioned Dumas by name. He basically said Dumas was the only French author with balls. What, no Flaubert?

At one point in his teens, REH thought Cabell was the greatest living writer, BTW.

-

We know for a fact that Leiber read SALAMMBO, however. In fact, it influenced the creation of the Gray Mouser.

-

It was very sad as an adult to find out that one greatest fantasies ever written and a childhood favorite of mine had been studiously ignored by our so-called “betters” back into obscurity again.

How dark and lonely they must feel inside to keep shoveling their books of dung over works of beauty like this and many others.

Unlike The Nightland, there is an excellent modern copy of The Worm Ouroboros available in the Dover paperback with the red cover.

I am pleased to see that William Morris’ Wood Beyond the World is to see a Castalia review. Hopefully also The Well at the World’s End?

Is John Wright a fan of George MacDonald too?

HPL was a huge fan of the novel:

Here’s a good post that has quotes of praise from many fantasy stalwarts:

http://www.isegoria.net/2012/02/the-worm-ouroboros/

Leiber considered it the best fantasy in the English language. The post does a good job of examining the profound impact of Shakespeare and other Elizabethans on Eddison.

It’s oddly like an Oz book for grownups. You’ve got the same minutely-detailed costume descriptions, the interior decor heavy on enormous gems, and of course the same sense that nothing will ever really change.

I don’t recall where I read it, but one reviewer described some of Eddison’s names — Goldry Bluzsco in particular — as sounding like pure Lilliputian.

Lessingham appears in Eddison’s Zimzimavia trilogy, also fantasy but set in Europe, which might be worth a look. The style is still highly elevated but it’s different from the above, more like the flashing of rapiers. Here is an example, torn from A Fish-Dinner in Memison.

Queen of Hearts: Queen of Spades: ‘Inglese Italiano’: the conflict of north and south in his blood; the blessing of that — of all — conflict. And yet, so easily degraded. As a woman’s beauty, so easily degraded. The twoness in the heart of things: that rock that so many painters split on. Loathsome Renoir, with his sheep-like slack-mouthed simian-browed superfluities of female flesh: their stunted tapered fingers, puffy little hands, breasts and buttocks of a pneumatic doll, to frustrate all his magic of colour and glowing air. Toulouse-Lautrec, with his imagination fed from the stews, and his canvases all hot sweat and dead beer.

Eddison sustains this almost indefinitely, in this case another half dozen painters, then poets, then … It’s a remarkable feat.

“Each of these authors have the one distinction which no author after shares…”

“Each” should take the singular form of the verb. So each of these authors has, not have, a distinction.

“without the crutch of having other books the reader also likes act an introduction”

I think you mean act as an introduction.