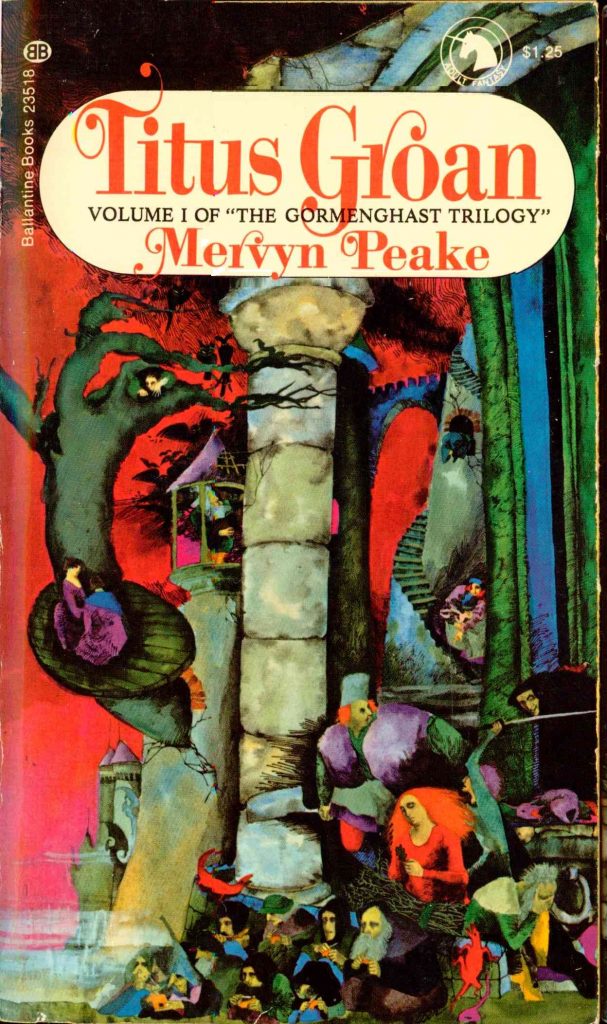

The Lost Works columns propose to review the authors of Ballantine Adult Fantasy series, as it contains the backbone of what an older generation read and understood fantasy fiction to be, and what, until recently, all fond fans of fantasy would have recognized as their shared core of works.

The series proper begins with certain precursor books. These bore the unicorn logo on their reprints, but not on the original printing. Only five authors are included: J.R.R. Tolkien himself, E.R. Eddison, Mervyn Peake, David Lindsay and Peter S. Beagle.

Lin Carter was the editor. He undertook the herculean task of rescuing from obscurity fantasy books forgotten in the flood of so-called realistic fiction that was in fashion with the socially conscientious mavens of literature before J.R.R. Tolkien brought widespread attention back to fairy stories.

Sadly, either due to the passage of time or the sour tastes of our own current crop of mavens, these books have largely fallen once more into an undeserved obscurity. The difference is that the current deluge is not of so-called realistic fiction but rather of so-called fantasy fiction. To many a reader (myself included) this current crop seems only partly fantastic. They include works set in magical worlds but otherwise formulaic, dull, politically correct, and unsavory (either girlish hence too sweet on the one hand or grimdark hence too bitter on the other).

A regrettably large number of these works seem bent on eliminating, rather that inflaming, any sense of wonder, awe, and phantasmagorical.

Ironically, the particular author we turn to this day is Mervyn Peake, who is very much in this mood and theme. This is the least fantastic book that has ever been shelved with the fantasy.

I confess out the outset that TITUS GROAN is decidedly not to my taste, but I will try manfully to give an honest picture of its merit to anyone whose tastes differ from mine.

The book describes the lives and foibles, follies and vices, crimes and deaths of the ugly dwellers in the monstrously oversized castle Gormenghast, a Gothic pile that is crumbling, ancient, dark and vast beyond all measure.

There is nothing, aside from the sheer astonishing size and age of the castle, which involves any element of the fantastic, otherworldly, or ultramundane. Everything else in terms of plot, character, setting, style and theme is mundane in each sense of the word, or less than mundane. Far less.

The events in the book (I almost wrote the word “plot”) concern an assistant cook and sociopath named Steerpike who conspires to elevate his station in life.

He escapes from the grossly overweight and sadistic cook Swelter, climbs the endless walls for hours, and finds his way into a deserted attic. He seduces first a bratty and ugly teenaged aristo girl Fuchsia, and later tricks into his cause the two addle-headed, overweight, half-paralyzed and epileptic twin sisters who are members of the aristocratic family of Groan. At his urging, the sisters Cora and Clarice, for motives of sheer malign spite, burn the ancient an irreplaceable library of the current Lord Groan, Sepulchrave, which is his only source of pleasure in life. Steerpike arranges to rescue the family from the flames in order to appear heroic and elevate his stature.

Lord Sepulchrave goes mad after the loss of his precious library, and is eaten by owls.

Steerpike fools the sisters by donning a sheet a pretending to be a ghost in order to terrify them into silence over their role in setting the fire, but later locks the idiot, half-paralyzed sisters in an abandoned chamber, where they starve to death. Or perhaps that happens in the second volume.

Fuchsia Groan is killed when she slips from a high window where she climbs to contemplate suicide.

Other events also occur, but since none seems connected to any others, I cannot recollect in what order they occurred, or in which book. I will recount them as best I can.

Flay and Swelter are the valet and cook in the castle, and they set about to murder each other. Flay is banished from the castle when he throws one of the Countess’s cats at Steerpike, but returns in secret to haunt its many empty rooms and deserted galleries, seeking the traitor he suspects is within.

Eventually Flay and Swelter fight with sword and meat cleaver in the Hall of Spiders, pausing only for the insane Lord Sepulchrave to walk by, muttering. No cause for the quarrel is given. I forget which one kills the other.

Other characters include persons as charming as any to be found in an asylum for the criminally insane. Irma Prunesquallor, the doctor’s sister is ugly but vain. Nannie Slagg is unintelligent and self pitying. Barquentine the son of the Master of Rituals is a dirty and lame misanthrope. The countess is an immense woman who lives in isolation, surrounded by pet cats and birds, showing no affection for, nor interest in, the child she bore. The boy is given to a wet nurse, Keda, who later commits suicide.

The finale scene of the first volume culminate with the lavish ceremony meant to invest the now one year old child Titus with the earldom. The ceremony is held on a lake. The child is handed a branch and a stone as symbols of his new authority, which he promptly and thoughtlessly tosses in the water.

This book is 338 pages, and the events go on for two more books of like size.

As for the setting, certainly the idea of a cyclopean and massive castle, crumbling with age, isolated, gigantic, with endless miles of chambers, galleries, dark passages, moldering squares and weathered towers is a striking image.

However, in this book, the role of the vast backdrop is to make the characters in the foreground appear smaller than they are. Nothing really comes of all this vastness, and it is never explained.

The castle rests in a valley surrounded on all sides by impassible barriers cutting it off from the outside world. Outside the castle is a single village of mud huts, who regard the Castle-dwellers (who remain always inside, except on ritual occasions) with awe.

The work is not fantasy. It is quite clearly meant to be taken as a work of grotesque humor mocking the ritual-bound pretensions of the useless aristocracy haunting Britain in the days of Mr. Peake’s youth, rattling around in their oversized mansions, ennobled neither by honest labor nor valor in war.

To make his point, he made the castle absurdly big and its dwellers absurdly petty.

Likewise, the work is not science fiction, since a science fiction writer would have troubled to explain where the food and people come from that support the castle, or why they support it, or what they do when they are not performing meaningless rituals. Or where the books in the library came from, or who weaves their clothing.

Indeed, the only labor mentioned at all in the volume is that carvings made by a special caste of hereditary woodworkers from the mud village whose years of painstaking labor go into making small statuettes that are immediately cast into an empty room in the castle and forgotten.

But such a logical question in a work like this would be as inappropriate as asking who bottles the beer or fixes the motorcar in WIND IN THE WILLOWS. These things are merely granted for the sake of the story.

But there is no world building here, no attempt whatsoever to invent a secondary world like the Hyborian Age of Howard or the Narnia of Lewis. Neither is the work set in our world. Not the slightest attempt is made to lull the reader into suspending his disbelief. The first question that enters the reader’s mind: who would build so vast an edifice and for what purpose? Is not even brushed aside. No smallest figleaf is given to explain it.

That matter is simply never addressed. In effect, the castle is the setting, and the past and the surrounding world are matters of utter indifference. As an experimental literary effect having a story with basically no setting at all may have some merit to it which is invisible to me. I did not get the joke, if joke it were.

As for style, allow me to quote in full a passage which is, as least to some, a favorite paragraph, called a crown jewel of literary craft. The writer is describing the reflections caught in a falling drop of water:

” A bird swept down across the water, brushing it with her breast feathers and leaving a trail as of glow-worms across the still lake. A spilth of water fell from the bird as it climbed through the hot air to clear the lakeside trees, and a drop of lake water clung for a moment to the leaf of an ilex. And as it clung its body was titanic. It burgeoned the vast summer. Leaves, lake and sky reflected. The hanger was stretched across it and the heat swayed in the pendant. Each bough, each leaf – and as the blue quills ran, the motion of minutiae shivered, hanging. Plumply it slid and gathered, and as it lengthened, the distorted reflection of high crumbling acres of masonry beyond them, pocked with nameless windows, and of the ivy that lay across the face of that southern wing like a black hand, trembled in the long pearl as it began to lose its grip of the edge of the ilex leaf.”

If this style of phrasing, as a long pearl of lake water plumply it slides and makes the reflection of high crumbling acres of masonry with nameless windows tremble, where the ivy is likened to a black hand, strikes you as poetical masterwork rather than as a pretentious cacophony inferior to the purple prose of H.P. Lovecraft, then by all means read this book to your full enjoyment with my blessings. I wish you much titanic and pendant burgeoning.

For myself, I will plumply sit in my chair and plumply not read it, and let the slithering, glistering glossolalia of awkward metaphor and jarring conjunctions begin to lose its grip on my interest.

I note that, for such a long description, nothing is actually described. Two colors are mentioned, the blue of quills and the black of ivy, but no shapes, sounds, smells. The air is said to be hot and the summer held inside the titanic waterdrop said to be vast. Perhaps these words in this order conjures some sort of visual picture in your mind, dear reader. Not in mine.

The only single word I enjoyed in that passage was spilth , which, to me has a delightfully precise savor of an archaic word: material that is spilled.

But no doubt I am a philistine. Let us quote another stylistic tour de force, this one where the two archfoes, the grossly overweight cook and the grossly paranoid valet, meet by the dark in the ruins of an ancient hall, weapons in hand. Their hatred is described thus:

” Swelter’s eyes meet those of his enemy, and never was there held between four globes of gristle so sinister a hell of hatred. Had the flesh, the fibres, and the bones of the chef and those of Mr Flay been conjured away and down that dark corridor leaving only their four eyes suspended in mid-air outside the Earl’s door, then, surely, they must have reddened to the hue of Mars, reddened and smouldered, and at last broken into flame, so intense was their hatred – broken into flame and circled about one another in ever-narrowing gyres and in swifter and yet swifter flight until, merged into one sizzling globe of ire they must have surely fled, the four in one, leaving a trail of blood behind them in the cold grey air of the corridor, until, screaming as they fly beneath innumerable arches and down the endless passageways of Gormenghast, they found their eyeless bodies once again, and re-entrenched themselves in startled sockets.”

Humor differs from man to man, and so what some find matter of endless mirth, leaves another cold.

Where others no doubt are smirking with uproarious chortles at the idea of Mars-red yet gristling eyeballs in ever-narrowing gyres sizzling down black hallways in anger, I am pedestrian enough to wonder how they might re-entrench themselves into the startled sockets at the hindpart of the paragraph if flesh, the fibres, and the bones had been conjured away in the forepart.

As Homeric metaphors go, it is somewhat Jamesjoycean.

As for the theme, the single thread running through the book is a grinding, ceaseless, tireless and jeering hatred of ritual, which the author here portrays only as those rites which commemorate nothing, engender no emotion, represent nothing, praise no gods, formalize no solemnities, and, in a word, do nothing and have no meaning.

Steerpike, the murderous sociopath, is presented as the only character in this book wise enough to be dissatisfied with the utterly meaningless formalities.

In order to create the artistic effect in support of his theme, in the same way that, for example, Ayn Rand portrays all socialists as utterly vacuous hatred-eaten losers, Mr. Peake portrays all rituals as utterly lacking in point or purpose, set in a castle utterly lacking in point or purpose, ruled by an allegedly aristocratic family who apparently has no estates to manage, people to rule, crops to grow, or services to offer any king.

Because no one has any duties or offices aside from utterly meaningless ritual, the truly utter meaninglessness can be placed at the center of all the lives of every character, to emphasize the author’s theme.

The normal duties of family life, normal affection, and so on, are also conveniently whisked offstage for like reasons. No mother is portrayed as enjoying raising a child, for example, nor any boy portrayed as enjoying courting a girl. No loyalty between underling and master is ever portrayed; no affection between husband and wife. Indeed, I am hard put to name any emotion which is portrayed in this long, glacial, cyclopean and Brobdingnagian book which seems human.

If there is some original story to explain that the once-vast castle originally housed a clan of ten thousand, but that a disaster cut off the valley from the world, and all vowed to uphold the now pointless rituals of their lost empire for fear of a peasant revolt, I did not see it. I assume any such explanation would spoil the joke.

In sum, the point being made by the story is that pointless things are pointless.

And the writer makes this point by meticulously avoiding any hint of action in the plot or any hint of any element of any personality development in any character that has any point.

I assume any reader who has secretly suspected all along that life is an ugly freakshow of nauseating grotesquerie, entirely void of love, honor, beauty, truth, or decency will leap like a salmon at the chance to read this book and find all his deepest notions reflected.

The version I read was marred by the ugliest interior illustrations I have ever seen. The illustrations were done by the author, and not by someone who knows how to draw, but mere unskillfulness of the pen cannot explain the dreary vision. The goal is disproportion and aberration. Imagine Gahan Wilson but without his sense of grace, perspective and proportion.

I am told that when the book premiered in 1946, it was met with rave reviews by ravished reviewers. Literary awards were heaped plumply upon it. Famed writers as Michael Moorcock magnify Peake as the unsurpassed paramount of fantastic literature.

To me it is a puzzlement. Similar praise from similar quarters was heaped with similar heedlessness upon Phillip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy when it came out. There is apparently a large market of fantasy readers who hate reading fantasy.

I trust the generous patience the readers will allow me to quote paragraphs from another book, once which explains both my personal judgment about TITUS GROAN and my suspicion behind the fulsome praises. As part of a psychological process to render him fit to greet and serve a race of demonic beings called Macrobes, young married man is locked in a room were all things are out of proportion and form no patterns, and he turns to look at the pictures adorning the walls.

“Some belonged to a school with which he was familiar. There was a portrait of a young woman who held her mouth wide open to reveal the fact that the inside of it was thickly overgrown with hair. It was very skilfully painted in the photographic manner so that you could feel that hair. There was a giant mantis playing a fiddle while being eaten by another mantis, and a man with corkscrews instead of arms bathing in a flat, sadly colored sea beneath a summer sunset. But most of the pictures were not of this kind. He was a little surprised at the predominance of scriptural themes. It was only at the second or third glance that one discovered certain unaccountable details. Who was the person standing between the Christ and the Lazarus ? And why were there so many beetles under the table in the Last Supper? What was the curious trick of lighting that made each picture look like something seen in delirium? …

“He understood the whole business now. To sit in the room was the first step towards what Frost called objectivity-the process whereby all specifically human reactions were killed in a man so that he might become fit for the fastidious society of the Macrobes [extraterrestrial demons]. Higher degrees in the asceticism of anti-nature would doubtless follow: the eating of abominable food, the dabbling in dirt and blood, the ritual performances of calculated obscenities.”

To me it is a mystery why, if a reader was hungering to read a story about mentally and physically defective characters treating each other with unending and immemorial hatred, contempt and ire, trapped in an endless castle of hateful yet unending and immemorial ritual, such a reader would also prefer a meandering and pointless plot; a foolishly jejune and pointless theme; a deliberately empty setting; and a prolix prose style to which the words pointless, pretentious, dull and awkward are the kindest descriptions to pen; not to mention the truly eye-jarring internal illustrations of amateurish ugliness.

I have read comics with equally negative themes penned by Alan Moore, but the plots there were tight, the characterization was crisp, and the draftsmanship was skilled.

I understand the craving for sour, cynical and negative books. But who wants his books, negative or no, to be poorly written and plotted? And who, seeing poor writing and plotting, praises it as genius?

Lin Carter surely did not think that fans of Lord of the Rings would turn from that trilogy to this with anticipation.

I suggest that the phrase “the asceticism of anti-nature” explains the mystery.

I am very glad to read this dismissive, indeed, contemptuous, review. I tried reading it once, and found it to be tedious and of absolutely no interest or merit whatsoever.

I shall now continue my previous practice of not reading it with a considerable sense of satisfaction in my literary instincts.

-

I second this praise.

Moorcock loved this and hated LotR. Case closed.

I commend you for taking one for the team, Mr. Wright. I was never able to finish this book, let alone its sequels. Considering the portion I did read and what I remember of it, your review seems spot on.

I had the same experience. I can’t wait to read Mr Wright’s review of something really, truly GOOD from the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series, by William Morris or someone like that. For a dirty proto-Commie, he seems to have been a decent sort, and I have vague memories of thinking The Well at the World’s End was pretty decent stuff. Although at 13, I was probably too young and inexperienced to really appreciate it the way I would now.

I should probably run down a copy again…

The last book in the trilogy, Titus Alone, is not like the first two books. It involves a young adult Titus leaving Gormenghast and its valley and ending up in a steampunkish world.

-

TPC says:

March 14, 2017 at 5:50 pm

“The last book in the trilogy, Titus Alone, is not like the first two books. It involves a young adult Titus leaving Gormenghast and its valley and ending up in a steampunkish world.”So the first two books should have been condensed to an introductory chapter in the third? Sounds like the re-edited Star Wars prequels.

-

Didn’t Peake’s widow finish that one?

“Put the girl in charge!” — Hudson

-

Yeah, I think the cover says “finished at Widow’s Peake”

-

Great review, I tried reading this turgid mess as a 14 year old with very restricted access to books – I was used to devouring everything I got my hands on. Not this one however. I was raised in the UK and was always puzzled by the high praise it received, for so many years.

For the record – I found the 2000 TV production entertaining, featuring as it did some great English comic actors including the genius Eric Sykes in one of his final roles.

Oh, and “who … fixes the motorcar in WIND IN THE WILLOWS” – isn’t part of the charm of the book the way the human and animal worlds interact? So the answer here isn’t too much of a stretch!

Thanks again for the wonderful review.

I remember seeing this book on bookshelves in homes and stores and thinking it was one of those books the right sort of person reads. I never read it, perhaps because I read a paragraph or two and stopped, or perhaps because the cover alone was enough to warn me off. For this I’m sure I silently thought less of myself.

I now honestly doubt anyone read it. It was just one of those things you needed to display, like a copy of “Godel Escher Bach.”

-

Please do not ennoble this pointless book by comparing it to a gem like Goedel, Esther, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid.

-

I haven’t read either book, so any comparison implied in my comment is unfounded in experience.

If I have maligned a good book, please blame the 1970s. In fact, you have my blessing to blame the 70s for almost anything, e.g. “Jogging.”-

No offense taken. But Goedel, Escher, Bach is a thoroughly enjoyable book, even though I entirely disagree with the author’s main premise (that hard AI is possible). It is a very fun disagreement, and I learned a lot along the way!

-

-

It has been 40 years or so since I read Mr. Peake’s trilogy, and it appears that my memory of it is crystal clear. Turgid, boring and depressing are the three words that come to mind when I think of the Gormenghast books, and I’m not sure why I bothered to finish all of them. TPC is correct, Titus Alone IS different from the first two books, but I don’t remember it being much better.

Moorcock is very good friends with Peake, and I admire that. But I remember Moorcock writing that he wrote the first Elric story while in the grip of a near-suicidal depression. I have to wonder if Peake’s trilogy had anything to do with that.

Peake’s basis was pre-revolution China, where he spent a portion of his childhood. Basically, Gormenghast = Forbidden City. Its utterly isolated, petty, custom-locked inhabitants equal those of Forbidden City.

Now, I don’t doubt that there’s this stab at British aristocracy there too, nor do I doubt that said stab was attractive to people like Moorcock. But, even with its British packaging, direct basis for novel’s setting was China in the twilight years of Manchu dynasty.

-

But China is interesting, so that is why he did not write that story?

Sigh.

Turgid, squalid, and boring; utterly lacking in any virtue as a fantasy work or a piece of entertainment.

Primarily beloved by those with literary pretensions who praise its virtues endlessly, and those who listened to such figures and like it because they are told they should.

-

On the other hand, I read a quote supposedly from C.S. Lewis saying that he liked it (it might have been on the cover of one edition, or in one of the amazon reviews, I forget which).

I read the trilogy a few years ago and I thought it was brilliant. It could be seen as a metaphor for life and youth struggling to assert itself against the dead weight of stone and tradition. The excerpts above don’t really convey the style, which uses extended metaphor and minute description to make time stand still. The characters are grotesque, but they have a great deal of pathos. It’s not the sort of thing I’d want to read every day, but it’s certainly more palatable than China Mieville’s insect-headed people and decaying slums.

It shouldn’t be judged by the standards of fantasy, because it’s not. The mood is something like a Jorge Luis Borges story. I quite enjoyed stories like “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius” even without knowing that it was a metaphor for totalitarianism.

-

The characters are (for the most part) sympathetic, and not all grotesque. Mr. Wright leaves out Doctor Prunesquallor, as virtuous a man as might be found, and Titus himself. Flay, Fuchsia, Nannie Slagg, and Irma are not quite grotesque either, just pitiable people trying to make their way in the world as best they can.

The advertising for the trilogy on various Ballantyne books intrigued me enough to pick up the copies from our local library. This was in the early ’70s when I was in high-school, and I remember reading them under the covers after lights-out, and thinking that they were endlessly fascinating and totally not the sort of thing I enjoyed reading, both at the same time. I reread the first two volumes every few years, just for the dense and visual prose.

The third volume, Titus Alone, verges more into general satire of the modern world, and I never particularly cared for it. I ascribe some of its lack of the earlier control on Peake’s failing health at the time. I rarely do the completist thing.

Of the concluding volume, Titus Awakes, which I picked up 3-4 years back when it came out, you can see where the page or so of Mervyn’s prose ends and Maeve takes over, and that she could not really write in a pastiche of her husband’s style. It ends up being everything I didn’t care for about Alone, without even the prose style. This was the one I found unfinishably bad.

-

Even Titus Alone is really an unfinished book, a sketch of what he intended. The prose in the first two books is far more polished and elaborate.

I would say the same thing to the detractors that I’d say to those who hated Star Wars in 1977. Maybe you went to the wrong movie. Maybe you ordered the chicken and got the fish by mistake.

I tried finishing it twice but unsuccessfully so.

In the end, I couldn’t figure out what people supposedly saw in it.

Mervyn Peake was not a terrible illustrator.

However, as Caleb says, he did spend 12 years in hide bound pre-revolutionary China, served in the war, became a war illustrator – which included seeing Belsen which had to have had an effect on him. He had Parkinson’s disease as well – that manifested itself later in his life having lain dormant.

I think this might be a dividing line within our friendly brotherhood, but if anything, you have undersold Peake and all of Gormenghast.

The carvings are not cast into an empty room and forgotten, for there is Rottcod, who invariably at 7, puts on his overalls and dusts all the carvings, the dust is never removed, (since that is not his job obviously) and piles up in the corners. He does this every day of the year at the same time every day. He maintains the candles and ensures they are always burning and the room is bright. At least he has a title, he is a Curator.

(John Doe goes to work every day, he operates a machine that stamps a particular shape in a piece of metal. He starts at 8:30 in the morning and finishes at 5 in the afternoon. He does this every day for 35 years, He is a machine operator team leader)

This is just from the beginning of the book, and in the same section Flay comes to visit, and says “Still here, eh?” as if one day he might visit, and someone who has been there for years or decades might suddenly not be there and no one know of it.

(“… then she would tell them … about her son who had been a bishop. And she spoke hesitantly, afraid they would not believe her. Nor did they all believe her, as it happened.” – not Peake as it so happens)

‘There should be no rich, no poor, no strong, no weak,” said Steerpike, methodically pulling the legs off the stag-beetle, one by one, as he spoke. “Equality is the great thing, equality is everything.” He flung the mutilated insect away.”‘

Swelter hates Flay because Flay thinks he is better than him just because he is only a cook. One day his taunting provokes Flay into whipping him in the face with a chain.

Flay hates Swelter, because the man never shows respect for his position as first servant, and when you have nothing else, your standing among the servants matters above all else. He sleeps on the floor outside his master’s room, he is literally nothing else but the first servant.

Despite the characters’ characteristics, there is more hope and charity in a thimble of Peake than there is in the entire oeuvre of Martin. And these characters are not easily forgot. There might be dozens, but if you apply the ol’ test of “describe these characters without saying what they do or what they look like,” then you will find it extremely easy. These characters have character!

It is no mere village that lies outside the walls of the castle.

“Gormenghast, that is, the main massing of the original stone, taken by itself would have displayed a certain ponderous architectural quality were it possible to have ignored the circumfusion of those mean dwellings that swarmed like an epidemic around its outer walls. They sprawled over the sloping earth, each one half way over its neighbour until, held back by the castle ramparts, the innermost of these hovels laid hold on the great walls, clamping themselves thereto like limpets to a rock.”

As to whether it is fantasy, that depends on whether you graft gothic fiction into the tree of fantasy. Personally, my tree of fantasy has roots in such luminaries as La Gerusalemme liberata and Orlando Furioso, The Green Knight and Beowulf. From these roots, there is a branch leading to gothic fiction and to include this most gothic of gothic fiction suits me well.

I read the first book a while back upon the recommendation of a co-worker who wanted to join my long running Dungeons & Dragons group.

I barely finished the thing and it was an effort of Will to do so. It is not brilliant; it reels in being dull. Nearly every time I read someone put it on a list of Best Fantasy or some such thing, I disregard there opinion, and likely all forthcoming opinions.

I find it similar to my reaction to “comedian ” Andy Kaufman. The most self-indulged, unfunny man to ever carry the designation of comedian and people still swear he’s the funniest thing ever and people who don’t get it just aren’t very smart. And they can see the Emperer’s New Clothing too.

Jackasses.

Should have gone with Alan Lee’s illustrations.

http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-YppYmmYMZVU/UryvlQiUigI/AAAAAAAACyA/kmW8iah4QbI/s1600/house+of+hours+4.jpg

Calls to mind Minas Tirith, in the long years of decline before the return of the King.

Mr. Wright, if you’re still here, have you ever encountered a little book called The High House, by one James Stoddard? It is also about an enormous house bound tightly by ancient rituals, though these rituals are good and necessary and beloved, and menaced by an anarchist, though this anarchist is recognized for the evil he commits; like Peake, Stoddard drinks from the well of the classics of fantasy, though unlike Peake he does not declare those waters poisoned. It is a delightful book, most certainly written in response to Gormenghast, and though a little awkward in places reminds me more of your Iron Chamber of Memory (if not William Morris) than anything else published in recent years

-

If I’m not mistaken, two gentlemen are acquaintances and friends (as well as massive Hodgson fanboys), so I think that it is fair to assume that Mr. Wright is familiar with The High House.

Titus Groan is a moody surrealist gothic, and as such it is pretty damn good. So, I think that your review is misguided and needlessly harsh. This has more to do with novel’s unfortunate classification within fantasy genre an the way in which it is still mentioned alongside Lewis and Tolkien, and I can sympathize with you and other who might’ve felt misguided and disappointed with it.

As a kid, I liked the characters and their Dickensianesque names. I just wanted them to have been in a more interesting book.

In the early 2000s in the tabletop RPG community, much fooferah was imbroglio’d over a self-published amateur game called F.A.T.A.L., which stood for “Fantasy Adventure To Adult Lechery”. Marketing itself as an “adult” game, it was a clunky heartbreaker of a rule set distinguished only by how much of its content was perversely pornographic — I will skip details and allow the interested to seek out their own reviews. My own thought, on reading about the game, was a moment of peculiar insight: it was as if someone had taken all the bad sex and violence jokes that occur whenever teenagers of any stripe get together (we’ve all cracked horrible gags once in a while), over thousands of groups and hours, and pulled it all together into one book.

The Gormenghast trilogy has always sounded to me like it was trying to do the same thing for a particular and peculiar strain of British humour: that black absurdist nuttery that can veer from sheer nihilist misanthropy at one moment to outright farce at the next. (The series Black Books, which I have been watching on Netflix, is another exemplar of said humour, and a very funny one.) I don’t think Peake ever imagined anyone trying to engage with it as a “subcreation” in the way Tolkien or Howard did.

And since, as the emperor observed while washing the jester’s blood off his hands, humour is impenetrably subjective, it does not surprise me that the Gormenghast books would be among those works utterly insusceptible to criticism. Perhaps by design; I have always semi-seriously believed that most of Samuel Beckett’s work was a conscious joke on the literary establishment, and this sounds like much the same thing, i’faith.

The first book of _His Dark Materials_ was a delightful fantasy. The author’s anti-religious animus was clear enough, but it did not detract from my pleasure.

The second book raised the hairs on the back of my neck. I had a powerful impression of uncleanness from it, and set the series aside with a shudder. I can’t point to any single incident in the book that gave this impression, it was something in the tone of the whole thing.

Nothing I’ve heard about the third book has given me any desire to revisit my decision.

I tried to read it.

I’d put most of the semi positive reviews down to virtue-signalling, or to intellect-signalling, or worse to love of the evil.

Comparing the response to Pullman seems a fair cop. I do wonder how many of the positive comments here thought Pullman good, instead of a despicable, if somewhat talented freak.

-

Pullman’s grasp of theodicy is about at the level of a bright 11yr old, if that.

-

He doesn’t even attempt theodicy, largely because his atheology, to coin a barbarism, is so grotesque.

The first book, as I said, I quite liked, despite the author’s hobby horses. The second one felt slimy and perhaps even demonic.

And no, it’s not just because he depicts God as evil, and the demons as righteous rebels. Stephen Brust’s book _To Reign in Hell_ basically does that, and it’s readable though far from great.

Pullman’s work is something else again. There’s a ferocity in the way he lies about good and evil that turned my stomach and made me fear for the man.

-

His cosmology isn’t “atheist” at all. There IS a “God” in his cosmos. He simply explains the evil in the universe as originating in that “God”. A Manichean/Gnostic view, basically.

-

Mr. Wright, would this be a case where you would say that, due to the objective nature of Beauty, to enjoy this book would be a mark of evil inclinations, as you said of Joe Abercrombie’s work, or is it something where tastes can reasonably differ?

I admit the setting sounds rather fascinating to me. The characters, not so much. Someone needs to be true and noble.

I read this in my late teens, and it made me feel suffocated and miserable… it was one of those books that ‘everyone’ said was a classic, and I felt I ought to like it.

I was also reading Samuel Beckett and Harold Pinter at that time – and they inhabit the same thought-world.

Nowadays, I would say the problem is not literary, but that these are evil works – they are (in a paradoxically fashion) actively promoting the sin of despair.

-

“Perhaps my best years are gone. When there was a chance of happiness. But I wouldn’t want them back. Not with the fire in me now.”

-Samuel Beckett, Krapp’s Last Tape

Since I do not think Mr. Peake had beauty in mind when he wrote it, I demur from answering the question. TITUS GROAN is a satire, a parody, something meant to appeal to the bleak and absurd humor of the gallows. It is hardly a criticism of an ugly work to say it is meant to be ugly.

But I will make an observation.

Those who enjoy this work honestly, and see some merit in it I cannot, might regret that my eye is not sufficiently trained in the arts to see what they see, but would not argue the point or cast blame. To them, it would not be a virtue to like the book nor a vice to dislike it.

But those who like the work because of its unrelenting bleakness and jeering contempt for all things human, they would indeed be hasty to call dislike of Peake a vice, and they would attack the person of the critic who criticizes the work, and not address the criticism. They regard dislike of this cherished masterwork as blameworthy, a sign of moral or mental failing.

Those people would be ones who should be regarded with some suspicion, and their words taken skeptically.

Well, Mr. Wright, I at least look forward to you write up on Lindsay. I recall reading your praise for “The Voyage to Arcturus” in the past, that you saw qualities in it in spite of it being steeped in Lindsay’s nihilism and anti-Abrahamic Gnosticism. Much like Tolkien and C. S. Lewis praised it back in the day, in spite of that.

GORMENGHAST is a character study of profoundly warped and stunted people, but it never comes across as misanthropic. The castle itself seems to exert some evil influence. The whole point of the story is that Titus escapes from it and goes out into the world and never looks back.

The primary villain, Steerpike, is portrayed quite unsympathetically. He destroys for the sake of destruction. His ambition and energy makes him seem heroic to Fuchsia, but it only serves to underscore his villainy. He causes Fuchsia’s death and is eventually unmasked and killed by Titus.

The castle is just a castle. It’s not a metaphor for British society or anything else. It is definitely NOT satire. Nor does it belong to the “filth and depravity” school of literature.

It’s grotesque, but in a way that’s beautiful rather than disgusting. It’s a bizarre, claustrophobic, insular, surreal world. It excels at creating a particular mood.

Most of my favorite books tend toward the heroic, the realistic, and the mythic. GORMENGHAST is a major exception. What sets it apart is the quality of the execution.

-

Well said, Fenris, but I’m not sure I agree about it being full of profoundly warped and stunted people. Your comment ‘The castle alone seems to exert some evil influence’ seems to be the important point. To me most of the characters were not profoundly warped or stunted, but rather ordinary people, whose petty faults in the claustrophobic atmosphere of Gormenghast doomed them. Take them outside Gormenghast and Fuchsia would merely be another self-obsessed teenager, Cora and Clarice a pair of social climbing old maids and so on.\

All in all, it’s one of those books I admired at the time but am not too keen to reread. And while I liked Titus Groan and Gormenghast I never even managed to finish ‘Titus Alone’.

-

“It’s grotesque, but in a way that’s beautiful rather than disgusting. It’s a bizarre, claustrophobic, insular, surreal world. It excels at creating a particular mood.”

Isn’t that how Milo described Berkeley?

There is a certain quality… how do I explain.

When you read the prose of Peake and then read the prose of Lovecraft, and while they are similarly purple in prose, one is energy-sucking and the other has drive, power…

When you read Pullman and in the first couple of pages the Plucky Orphan has Hidden In a Cupboard and Overheard The Villains Speaking on a Crucial Plot Detail that Sends Her On a Fabulous Adventure… and somehow he makes that suck all the energy out of the room. Even though I’ve read that lead-in a dozen, if not a hundred times before, somehow he steals the thrill from it and leaves it dead.

As a member of one of those long-running epic 40-year D&D campaigns where sets of mighty heroes retire and inspire future generations, I have had cause to occasionally reread 1st and 2nd editions of the various D&D books. And, whatever their failings might be when compared to our more modern gaming knowledge; the sheer love and excitement burns through the prose. The reader knows the author loves what he’s doing, loves what he’s trying to transmit, to give to you as a gift. Yet somehow, however much we might like Mike Mearls as a person and admire his technical skills, no matter how well the game might play when run by a good gamemaster… somehow the 5th edition has lost that burning love when you read it.

-

I’ve seen many people praise Gygax’s prose, but I’ve always been turned off by the man’s insufferably pretentious style.

He spends so much time in the DMG defending his design decisions as the One And Only True Way Of Doing Things that I honestly wonder if he loved the game or his representation of the game in rules. I’ll take the 5e books any day.

Don’t get me started on the man’s fiction. It’s actively awful.