There’s an interesting comment over on Playing Dice With the Universe from an aggravated Dungeon Master aggravated at his players complaints of his railroading ways:

There’s an interesting comment over on Playing Dice With the Universe from an aggravated Dungeon Master aggravated at his players complaints of his railroading ways:

My only real concern as a 1e DM is the cries of “railroading” when players try to leave the the established play area. We’re playing a game, the context of the game has been established in (pick your module, etc…) the pre-determined area by the DM.

If the player continuously tries to not abide by those established boundaries, I reserve the right to use means that move the game along the prepared outline or end the game (for that player or as a whole).

Yes, players want to make choices and DM’s want to watch the game unfold as prepared. When either starts forcing changes beyond that preparation, it hoses the whole experience up.

This is exactly wrong.

Yes, it is possible to play a standalone module pretty well as written for a fairly long period of time. But that is not the type of play that the classic role-playing games were designed to create. And while many game masters can cobble together a campaign by moving the players from one prepared module to the next, that is not the only way to play.

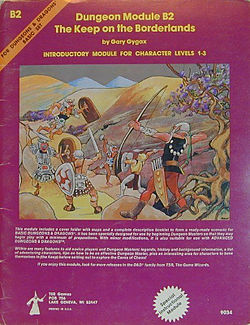

If you run the classic module Keep on the Borderlands, the players have a lot of choice when they get to the Caves of Chaos. There’s so much there to choose from! But that is not the only choice they have. There’s the wilderness area surrounding the Keep. They may choose to go investigate the Mound of the Lizard Men instead. Or they might tackle to Raider Camp. Or they might fall afoul of the Mad Hermit.

And even that’s not the only choice they have. Many players love to explore the civilized area within the Keep itself. They really want to know who is in the Tavern. They want to play out conversations with the people that are there– sometimes for clues and rumors, other times just because it’s fun. And then there’s the Chapel– is the cleric there any help…? Is he up to something? What’s going on? And what does it take to meet the Castellan?

It’s like three different games at once! Think about the variety that’s entailed with this and how neat it is that the players can determine for themselves what proportion of town, wilderness, and cave interactions they dedicate to the session. The combination of a range of options plus the freedom of the players to choose means that you will get exactly the sort of game that is most entertaining for them every single time!

And yes, it’s possible for a referee to get caught flatfooted. What if he prepared for the dungeon crawl and didn’t make any effort at all to review the other areas? That happens. And is it really so hard to skim a keyed entry and then improvise something on the spot…? Hey, that’s something referees have to do no matter what. That’s synonymous with game mastering.

But what do you do when the players start asking about stuff that’s off the map edge. Is it really that much harder to just make something up…? Not really. Oh, but you already know what’s going to happen when you do. You will make up something downright silly, but it will strike the players fancy somehow anyway. And they’ll start talking about it… and then decide to go do this thing that doesn’t even exist yet.

The commenter over at Playing Dice with the Universe says that that is the exact point where “he reserves the right to use means that move the game along the prepared outline or end the game.”

I would argue that the game had never even begun to begin with in that case. Because the entire point of role-playing games is that they can handle unplanned and even unimaginable circumstances and keep on rolling into something that is more interesting than anything anyone could have worked out as a perfectly engineered adventure module. That’s the thing that they do that makes them different from every other type of game. That’s the lightning in a bottle that caused role playing games to garner the cult following that they spawned way back in the seventies.

But let’s be honest here. When you cease being a neutral arbiter and use your powers of referee fiat to put the game back on track after it goes off the rails, then what you’re doing is railroading. And while the players may have some agency within the narrow scope of what is explicitly laid out in some adventure module, they clearly don’t have it where it counts.

Maybe the module is going to be way more fun than the sort of thing you end up making up on the spot. Or maybe the players are the ones that are best positioned to be the judge of that. And the referee has simply decided to not perform his function!

This is why my preferred form of module are location-based adventures without any pre-determined plotline that one can just drop onto a hexmap and let the players decide if they want to explore it.

-

That’s why B2 and T1 were great modules: you could use the Keep or Village as a base of operations or resupply and let the Party do as they will. The modules were seeds, or rather shells, for the adventure.

Caves and Moathouse never get visited? So what? Other adventures await!

The DM in question here needs to buy some graph paper and a pencil.

“My only real concern as a 1e DM is the cries of “railroading” when players try to leave the the established play area…I reserve the right to use means that move the game along the prepared outline or end the game (for that player or as a whole).”

Is that a gold-plate or a pewter-finish pocket watch you got there, Mr Conductor?

Looks like gold-plate to me.

The design of your maps can lead to railroading as well, or your module linearly moves from Room 1, to 2, to 3, to … . Some useful articles:

The Alexandrian: “Jaquaying the Dungeon”

Dragonsfoot/ENWorld poster “Melan”: “Dungeon Mapping”

There is a difference between being prepared to run a module (or an adventure, or a dungeon, or however you want to put it) and being prepared to run a game.

The commenter you quote isn’t prepared to run a game. The line, “established in the pre-determined area by the DM” makes that clear.

Role Playing Games do not have pre-determined areas. That’s what makes an RPG an RPG, rather than a board game.

In “Clue” players take on the identities of fictional characters and interact with the environment and other players in order to accomplish the goal of solving a mystery.

But it’s not an RPG, because you can’t do anything other than solve the mystery, and you can’t leave the house. Miss Scarlet can’t use the lead pipe to break open the window of the Conservatory and escape into the back yard. Colonial Mustard can’t shoot Professor Plum with the revolver.

You could make an RPG based on Clue (I think it would be pretty cool, actually, make up pre-gens of the characters and put them in the house with the late Mr. Body) but if you did, you’d have to be prepared for the characters to go off on their own and do things entirely unrelated to finding a murderer.

Otherwise you’re just playing Clue with more rules.

Jeffro: for TSR’s D&D, specifically AD&D, how many of those classic modules were written initially as tournament modules, then converted to generic modules for sale to the general gaming community?

Tournament modules are designed to be linear in nature (to at least some degree) for scoring purposes and time limitations of the tournament setting at a convention. A classic example is the TSR AD&D 1E A-series “Slaver” modules.

I don’t doubt the concept of “tournament module reworked to produce commercial TSR product” is significant influence on commercial and independent module design through the 1980s and up to today.

Many post-1970s gamers learned from the modules they purchased, not from the literature they read.